BBCcom_Content_Index_for_September_28_2023.txt

'I had no idea it would snowball this far' Why a Brazilian favela facing eviction decided to go green.txt

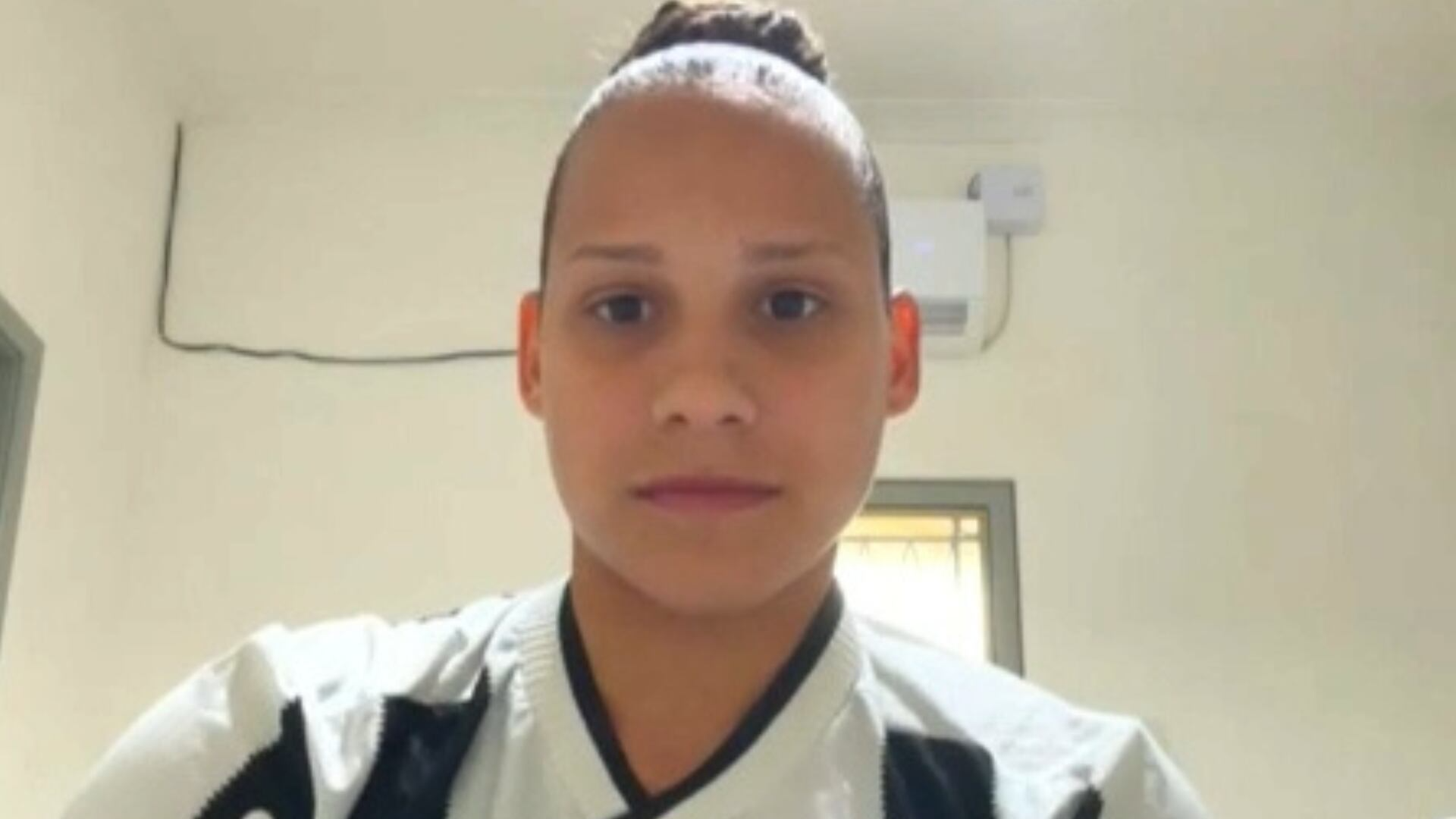

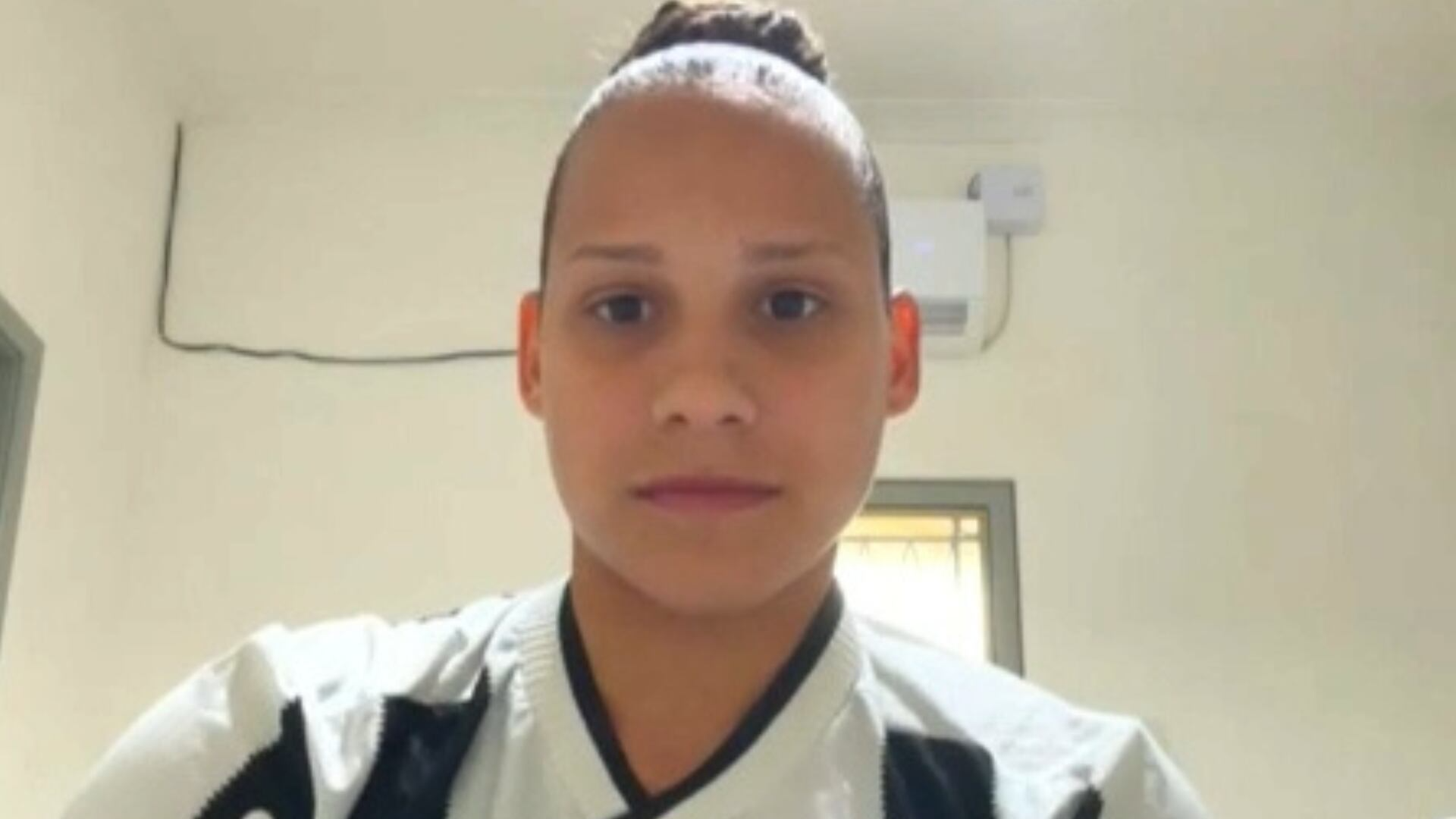

'I had no idea it would snowball this far': Why a Brazilian favela facing eviction decided to go greenSkip to contentBritish Broadcasting CorporationRegisterSign InHomeNewsSportBusinessInnovationCultureArtsTravelEarthAudioVideoLiveHomeNewsIsrael-Gaza WarWar in UkraineUS & CanadaUKUK PoliticsEnglandN. IrelandN. Ireland PoliticsScotlandScotland PoliticsWalesWales PoliticsAfricaAsiaChinaIndiaAustraliaEuropeLatin AmericaMiddle EastIn PicturesBBC InDepthBBC VerifySportBusinessExecutive LoungeTechnology of BusinessFuture of BusinessInnovationTechnologyScience & HealthArtificial IntelligenceAI v the MindCultureFilm & TVMusicArt & DesignStyleBooksEntertainment NewsArtsArts in MotionTravelDestinationsAfricaAntarcticaAsiaAustralia and live blackjack vip slotPacificCaribbean & BermudaCentral AmericaEuropeMiddle EastNorth AmericaSouth AmericaWorld’s TableCulture & ExperiencesAdventuresThe SpeciaListTo the Ends of The Earth EarthNatural WondersWeather & ScienceClimate SolutionsSustainable BusinessGreen LivingAudioPodcast CategoriesRadioAudio FAQsVideoLiveLive NewsLive SportHomeNewsSportBusinessInnovationCultureArtsTravelEarthAudioVideoLiveWeatherNewsletters'I had no idea it would snowball this far': Why a Brazilian favela facing eviction decided to go green23 August 2025ShareSaveLottie WattersShareSaveLottie WattersThe garden in Vila Nova Esperan?a favela (Credit: Lottie Watters)In Brazil's crowded favelas, green space is hard to come by, but this S?o Paulo community is showing how more sustainable favelas can give back to their residents."You have to remove the seeds before they flower."Maria de Lourdes Andrade Silva is showing me how she picks the buds off a flowering basil plant as she tends to a vibrant community garden in a favela in S?o Paulo, Brazil – South America's largest city. "If you leave it to flower, it'll use up all its energy and it will die," she says.When I visited this 0.5 hectare (1.2 acre) garden in Vila Nova Esperan?a favela in 2022, it was teeming with herbs, plants, vegetables and life. Today, it's been Silva's labour of love for more than a decade. Before Silva's efforts, it was entirely different: the disused space on the edge of the favela was piled high with rubbish and people would come here to dump things, she says.Originally from Itaberaba, Bahia in the north-east of Brazil, Silva – better known as LiaEsperan?a, or Lia "Hope" – moved to the favela in 2003 having never lived in one before.Home to more than 8% of Brazil's population, favelas – or Brazilian slums – are widespread informal settlements often situated on the periphery of major cities such as S?o Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. They are home to low-income populations and can be built precariously on unstable land such as slopes and hills. They are often underserved in formal infrastructure – meaning they can be especially vulnerable to climate impacts and risks such as landslides – and commonly don't have access to public services such as sanitation.We didn't have sustainability specialists to teach us how to preserve the environment, so we came up with the idea of creating a community garden – Maria de Lourdes Andrade SilvaIn 2006, Silva, who was working as a florist in S?o Paulo, learned there was a process in place to remove the families living in the favela. The community is located near – and what S?o Paulo's Public Prosecutor's Office considered within – an environmental protection area. Because of the litter and lack of sanitation services, the settlement directly impacted the local environment, so the prosecutor wanted to remove the settlement and the litter, restore and promote reforestation of the area, and incorporate it into the nearby Jequitibá Park. It meant 600 families in the favela faced eviction."I thought, 'I have to do something to not lose my home nor anybody else's,'" says Silva.Along with other members of the community, she set out to clean up the area and prove in the process that favela residents could benefit their local environment.Igniting changeSilva guides me through the garden, ducking under giant passionfruit vines and past uniform rows of seedlings. "Before, the community was completely full of rubbish," she says. City waste collection didn't reach this informal settlement, so in 2006 she instigated a community clean-up which became a regular collective effort. The community also built a waste bin shelter to dispose of waste across the whole favela.Getty ImagesVila Nova Esperan?a has become an award-winning example of a "green" favela (Credit: Getty Images)Silva argues that people don't intend to degrade the environment but do it because they don't know any different or lack access to necessary waste collection services.In 2013, at a community meeting with over 200 residents a year after a court had ruled against a civil public action to evict the community, Silva warned that they still needed to find a way to coexist with the natural environment or face being forced from their homes. "We didn't have sustainability specialists to teach us how to preserve the environment, so we came up with the idea of creating a community garden," says Silva. "And with the garden, we would bring environmental education.""I thought it was a great idea," says Cícera Maria Lino, a resident of Vila Nova Esperan?a who joined the efforts against eviction and has volunteered at the community garden since its beginnings. She grew up growing vegetables in the countryside of Pernambuco in the north-east of Brazil and moved to the favela in 2002. "It was a big fight [against eviction], and we didn't have energy at the time. But we got it with Lia."84% of favela dwellings in S?o Paulo have no open space surrounding them at allNot everyone was immediately onboard with the garden project, however. Some residents felt the land should be used to build more houses or sold to bring in money to the community, locals tell me. Ultimately, though, when the community held a vote, the majority were in favour of the garden, they say. At the beginning, some five or six residents started planting vegetables. "I started out of necessity," says Silva. "I had no idea it would snowball this far." The community began contacting NGOs and universities to help them build a sustainable community.Maria de Lourdes Andrade SilvaBefore the community, the area which has now become Vila Nova Esperan?a's community garden was used as a dumping ground (Credit: Maria de Lourdes Andrade Silva)When Batista Santos, a security guard originally from Bahia, moved to Vila Nova Esperan?a from a neighbouring community in 2014, he heard about the project but didn't immediately get involved. "I was working 12-hour days... and working in the garden is hard work," he says. It wasn't until the pandemic hit in 2020 and he became unemployed that he started to participate and realised the value of the garden, he says. "The space today is marvellous and beautiful... It's really changed my life."Now Santos is vice president of Vila Nova Esperan?a's resident's association, which organises meetings and tries to address issues to improve the community (Silva has been the association's president since 2010, after leading the community's fight against eviction).The battle for spaceGardens like these are a rarity in Brazil's slums. Favela populations are growing, with nearly five million more people living in them in 2022 compared with 2010, a rise driven by a lack of affordable housing in Brazil's large cities, low wages and rapid urbanisation as people move to the cities in search of jobs and opportunities.As favelas grow, they not only expand and encroach on (often protected) land, but their population density increases, meaning already highly populated areas become even more crowded. The population density of favelas in S?o Paulo is four times that of the formal city.As informal settlements expand, it's hard to keep any space vacant in these areas – let alone green space, explains Alexandra Aguiar Pedro, a S?o Paulo-based urban planner who conducted research on creating urban gardens in favelas in 2020 while working for the housing secretariat of S?o Paulo City Hall.If people have gardens that are providing food, then they are able to feed themselves – Theresa WilliamsonIn fact, 84% of favela dwellings in S?o Paulo have no open space surrounding them at all, a 2016 study found. Because they are built and expanded informally, says Pedro, there is rarely – if ever – planning to integrate green or open spaces. Just one type of recreational space is common in favelas: "When you look in these areas, the only empty spaces are the soccer fields," says Pedro.Space needs to have value to residents if it is to resist these expansion pressures, says Wolfgang Wende, a researcher in landscape, ecosystems and biodiversity at the Leibniz Institute of Ecological Urban and Regional Development in Germany. "The only way to do that is to create a kind of sense of ownership by the neighbourhood, so that they really feel responsible for these open spaces." A prize-winning transformation"Favela upgrading" is the Brazilian government's attempt to integrate favelas into the formal city with public services and infrastructure and formalise land registration. But critics say these attempts can end up doing little to alleviate persistent issues of poverty that push people into favelas in the first place. "Only the initiatives which involve local people work," says Pedro.Getty ImagesChildren play football on a pitch at Tavares Bastos favela, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Favelas often lack space for recreation – other than football pitches (Credit: Getty Images)Silva says Vila Nova Esperan?a's greening project has succeeded due to the involvement of the entire community. Too often, she says, the government arrives with engineers, architects and a top-down approach that doesn't involve the local community. "People need to have a voice."However, responding to these criticisms, Guilherme Sim?es, the Brazil's national secretary of urban peripheries says it is essential that governments invest in urban infrastructure, calling it "a fundamental condition for access to decent housing, basic sanitation and other social rights". Public participation, he agrees, is fundamental to ensuring that such interventions are successful, and he points to the Brazilian government's Periphery Life programme, which includes a participatory action plan as a mandatory element for such interventions.Vila Nova Esperan?a's project has received recognition across Brazil and globally. In 2014 it was awarded the Milton Santos prize for social development by the municipality of S?o Paulo. Following this recognition, much of the community has now been given formal water, sewerage and electricity connection and asphalt roads.Still, a battle against eviction in the community has been ongoing for several years. In 2011, things came to a head when armed men showed up to forcibly remove families, although it is not clear who they were working on behalf of. The residents resisted, although over 100 families agreed to leave following the ordeal. But most Vila Nova Esperan?a residents remained and in 2012, a judge ruled in their favour and determined they could stay. Motivated by this ruling, they moved forward with the garden and in 2013 began cultivating carrots, lettuce, beetroot and dozens of other fresh vegetables, fruits and herbs. Anyone is welcome to volunteer, receiving harvested food in return. The remainder is sold at an affordable price to other residents.Gardens like these offer communities "food sovereignty", says Theresa Williamson, an urban planner and executive director of Catalytic Communities, a non-profit that manages the Sustainable Favela Network in Rio de Janeiro. "If people have gardens that are providing food, then they are able to feed themselves."Santos says the garden has made a difference to him and his family. "To this day, the garden helps a lot of families here," he says.Getty ImagesSilva and other community members build a house with clay in the favela in 2020 (Credit: Getty Images)Following the garden's success, the community moved forward with their next undertaking – a library. They used a simple traditional wattle and daub method from the north-east of Brazil to construct the library, sourcing recycled wood and materials wherever they could and only buying new supplies when strictly necessary. "That was our first sustainable construction," says Silva.A community kitchen followed in 2018 and they began teaching people to prepareplantas alimentícias n?o convencionais (non-conventional edible plants, often referred to as "pancs"). These are Brazilian fruits, leaves and flowers with high nutritional value that grow easily in small spaces, such as lambari (also known as the goldfish plant) and sweet potato plant leaves.Pancs offer exciting potential for communities with limited space, says Williamson. "They just freely grow and you can grow them in your windowsill."With the kitchen came entrepreneurship. Community members began to make and sell cakes as well as "marmitas" – hot lunch deliveries, a staple in Brazil – which brought in income.More like this:? The Indian cafes where you can pay in rubbish? 'Meadowscaping': The people turning their lawns into meadows? My quest for a climate-friendly family diet"We brought food security, we taught people to eat healthy food, [and] we reduced the number of visits to the hospital, because we have a lot of medicinal plants," says Silva, explaining how the community uses plants to help to treat fevers and flu.Today, the government offers employment opportunities at the community garden through the Agriculture Work Operation Programme, which seeks to expand urban agriculture – a stark contrast from the attempted evictions over the past two decades. The community kitchen provides healthy weekday meals to more than 200 families using food from the garden, and the community space hosts skills workshops and courses such as sewing and crochet. Women attending these workshops tell me they hope to earn an income using these skills once they complete their courses.A bottom-up approachMost of the volunteers in the garden and kitchen are women, and the initiative has also provided them with a safe space, says Silva."You get these ripple effects that are really strong when the community gardens are run collectively by women," says Williamson, who has worked with women-led gardening collectives in Rio de Janeiro favelas. Women support each other and share knowledge on employment, household issues and how to raise their children, she says.Lottie WattersSilva shows off a giant passionfruit grown in the community garden (Credit: Lottie Watters)All the volunteers I spoke to when visiting the favela in 2022 told me that tending to the garden benefits their psychology, health and mental health. "I always like to come here. I come whenever I can," Lino told me.In order to share their knowledge further and assist other communities, in 2018 Silva set up the Lia Esperan?a Institute to share knowledge. She has also travelled the country sharing her lessons and learnings with other communities, favelas, schools and universities. One group she met with is Mulheres do GAU (Women of the Urban Agriculture Group), a collective of women who have moved from the north-east of Brazil to the east of S?o Paulo, where they run a community garden and kitchen at a nursery school.Carbon CountThe emissions from travel it took to report this story were 5kg CO2, as Lottie was in Brazil for other reasons. The digital emissions from this story are an estimated 1.2g to 3.6g CO2 per page view. Find out more about how we calculated this figure here.Today, despite the favourable 2012 ruling, the community still fear eviction. Further attempts persuaded more families to leave in 2022, says Silva."The fear, the insecurity, is constant and we have no guarantee of anything," says Santos. "But we're living in a space that we're taking good care of and preserving [the environment]."A spokesperson from S?o Paulo's public ministry of state (MPSP) tells the BBC that the case is currently in the sentence enforcement phase and it has held meetings with residents and relevant public agencies, especially housing association CDHU which MPSP says is "adamant and wants residents to move to housing complexes by them built [elsewhere]". It added that it is trying to keep the families in place but that this depends on the goodwill of the CDHU. However, it adds that "there can be no increase in occupation, as this is an environmental preservation area".The CDHU, however, told the BBC that the removal of families from the community is the result of a final court decision which followed the opinion of the MPSP, noting it has complied with the court decision and intends to continue with the agreement in recent petitions to remove the families and reforest the area.While no mention was made of the favela cleaning effort in the 2012 ruling, it was highlighted by councillors fighting for their case. Lino believes the garden is a key reason the community remains. "If it wasn't for the garden, they would have been able to get us out of here," she says. "The work that Lia has done has had a huge impact. There are people living here who don't value [the work that Silva has done] but they have no idea how good it has been for us all."Silva's part, though, she says it is the power of community she has learned through the project. "I can't do it alone," she says.--For essential climate news and hopeful developments to your inbox, sign up to the Future Earth newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram. Future PlanetEarthGardensSustainabilityEnvironmentCitiesFeaturesWatchSeven images that transformed our world viewWatch how the maps and images of our planet from above have changed over the last two millennia.30 Apr 2025EarthTen striking images of an Earth scarred by humansFrom a shipwrecking yard in Bangladesh to a river of iron dioxide in Canada, a deep dive in Ed Burtynsky's work.16 Apr 2025EarthBovine language: Studying how cows talk to each otherLeonie Cornips, a sociolinguist at the Meertens Institute in Amsterdam, turns her attention from humans to cows.19 Feb 2025Future PlanetRaja the elephant asking for a road tollIn Sri Lanka, a charming elephant cheekily halts traffic for treats. 29 Jan 2025EarthInside the hidden world of rhino romanceWatch two rhinoceroses involved in a game of 'kiss and chase'.24 Jan 2025EarthA mother tiger on a fierce hunt to feed her cubsWhile her three offspring take a leisurely bath, this Bengal tiger mother must find food for the entire family.16 Jan 2025EarthHow foxes outsmart world's heaviest raptor in quest for foodWatch red foxes challenge the Steller's sea eagle, the world's heaviest raptor, as they search for food in Japan.8 Jan 2025EarthMum saves baby seal with a clever trickWatch as David Attenborough reveals the unique behaviour of a mother seal to protect her pup in icy waters.31 Dec 2024EarthMountain goats: A death-defying battle to mateWatch the world's largest species of goat fight for the right to mate, teetering on the edge of perilous drops.17 Dec 2024EarthThe near miraculous escape of a cave swiftThe Tam Nam Lod Cave is home to over a quarter of a million swifts. But there are hidden dangers.12 Dec 2024EarthThese animal photos won funniest of the yearThe Comedy Wildlife Photography Awards held their annual ceremony, crowning the funniest animal photos of 2024.11 Dec 2024Future PlanetMeet the mudskipper: The remarkable fish that lives on landThe mudskipper is a fish that can leap with a flick of its tail. Watch a particularly agile specimen in action.3 Dec 2024EarthWatch the dramatic escape of tiny fish from deadly sharksThe Moorish idol, a dramatic little fish with dazzling stripes, adopts a clever strategy to save its life.27 Nov 2024EarthHow 17 wild New York turkeys took over VermontWildlife biologists released a few wild turkeys in Vermont in 1969. There's now a thriving population of 45,000.23 Nov 2024Future PlanetEarth tides: Why our planet's crust has tides tooHow do they differ from the ocean? A geophysicist breaks it down for us.28 Sep 2024Weather & scienceInside the world's largest hurricane simulatorAt the University of Miami, a large indoor air-sea interaction test facility measures the impact of storms.27 Aug 2024EarthIn Australia, sea lions help researchers map the ocean floorResearchers in Australia put cameras on sea lions' backs to help them map the elusive ocean floor.21 Aug 2024EarthThe deadly plants hiding in your gardenThe Poison Garden at the Alnwick Garden has around 100 toxic, intoxicating, and narcotic plants.20 Aug 2024NatureThe scientists drilling into an active Icelandic volcanoScientists are preparing to drill into the rock of an Icelandic volcano to learn more about how volcanoes behave.18 Aug 2024Climate solutionsEarth's spectacular and remote 'capital' of lightningWith storms occurring between 140 to 160 nights a year, it's no wonder the area is a world record holder.6 Aug 2024World of wonderMore from the BBC21 hrs agoThe controversial sweet that fuels NorwegiansKnown as 'the trip chocolate', Kvikk Lunsj has fuelled outdoor adventures for generations. So, what makes this chocolate so controversial?21 hrs ago22 hrs agoHow women's pockets became so controversialWhy do men's clothes have so many pockets, and women's so few? For centuries, the humble pocket has been a flashpoint in the gender divide of fashion. Is that finally set to change?22 hrs ago23 hrs agoEarth has now passed peak farmland. What's next?The world's use of farmland has peaked, bringing the chance to turn over more space to nature. How far could the trend go?23 hrs ago2 days agoCall for action over 'heart-wrenching' blue-green algaeA public meeting took place on Monday evening in response to the ongoing pollution crisis at Lough Neagh.2 days ago2 days agoThe road trip that celebrates a musical legendMany towns and cities along the Blues Trail have planned festivals, exhibitions and live music to mark the 100th birthday of the homegrown musical legend.2 days agoBritish Broadcasting CorporationHomeNewsSportBusinessInnovationCultureArtsTravelEarthAudioVideoLiveWeatherBBC ShopBritBoxBBC in other languagesFollow BBC on:Terms of UseAbout the BBCPrivacy PolicyCookiesAccessibility HelpContact the BBCAdvertise with usDo not share or sell my infoBBC.com Help & FAQsContent IndexCopyright 2025 BBC. All rights reserved. The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Read about our approach to external linking.